In September, I attended and presented at GikII 2023, a conference on law, technology, and popular culture. The idea of linking law in Max Gladstone’s Craft Sequence to social ontology and legal theory had been fermenting in my mind for a while, so this was the perfect opportunity to finally put that idea on paper (or, as the case may be, into a power point presentation).

In this blog post, I want to reproduce (parts of) my presentation and slides. Bear in mind that the talk was about 10 minutes, so naturally, there’s much more to be said about just about any part of this. But if I can show how law in the world of the Craft Sequence links to law, legal reasoning and legal theory in our world, I’m happy – and if anyone’s entertained as well, all the better. I know I had fun with this one!

First of all, what’s the Craft Sequence? It’s a book series by Max Gladstone, who is far better at providing a primer on the series and convincing people to read it than I could ever hope to be. For present purposes, the summary of “it’s your job, only with wizards” is the most relevant: in the world of the Craft Sequence, lawyers are, quite literally, necromancers/wizards.

The series is absolutely amazing, so I highly recommend it to anyone, especially anyone with a law background (although that may be my own professional deformities talking). Seriously, though, the first book I read starts with a junior law associate having to settle the estate of/resurrect a dead God. If that doesn’t get you interested, we might just have very different taste in books. Here’s more on the series.

Lawyers are necromancers/wizards called Craftfolk in the world of the Craft Sequence. Craft is a relatively new type of magic in this world, existing next to Applied Theology. Craftfolk can directly impact physical reality through (legal) claims and arguments.

In the world of the craft sequence, arguments, in particular legal arguments, directly affect and impact physical reality. A contract, for example, can physically bind and literally make certain actions impossible for the person who undertook the a contractual obligation to refrain from those actions.

Similarly, property claims make it physically impossible to take an item from someone who can convincingly claim that they have a title to that item – as Tara, aforementioned junior law associate does when arguing with a goddess. (Side note: there’s an interesting comparative law question in here, re: differences between common and civil law treatment of property vs personal rights, but that’s a whole other conversation.)

There’s a much more extensive account of how magic works in the world of the books on The Hidden Schools: part 1 & part 2. Not going to lie, I used those posts extensively in preparing this talk.

How does law in the Craft Sequence world compare to law in our world?

In our world, legal claims and arguments obviously don’t affect physical reality in the same way.

My favourite example to demonstrate this is somewhat autobiographical in nature: when I was a young kid, I lived near a zebra crossing over a busy street that separated me from the nearest forest. My mother tended to be quite worried about the cars on the street, while I was blithely unconcerned: there was a zebra crossing, so the cars were not allowed to hit me, so therefore they couldn’t. The last step in that chain of reasoning is where it goes wrong, obviously: that they weren’t allowed to doesn’t mean that the cars couldn’t physically hit me. (Fortunately, none ever did. Also, in my defence, I was a. young and b. German.)

So, clearly, a legal prohibition doesn’t lead to physical impossibility in our world. Law doesn’t affect our reality the same way it does in the Craft Sequence. That doesn’t mean, however, that law doesn’t shape or create reality in our world as well.

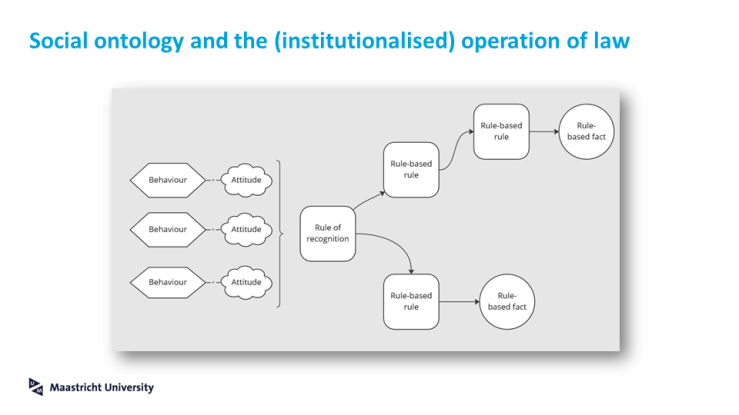

The image above shows a (very simplified) view of how law operates in our world, according to a socio-ontological, institutional view of law. There are a few parts of this picture that are relevant for present purposes.

First, the left-hand side of the picture: when certain behaviours (such as norm-compliance, recognition of certain consequences) and attitudes (such as believing there is a norm) coincide, social facts (“this is a border”) or social rules (“you ought to take your hat off in church”) are created. In other words: we collectively create social reality. (For the connoisseurs: social reality is ontologically subjective, but epistemologically objective or, I would say, inter-subjective.)

Then, the right-hand side of the picture: part of what is created in this way (that is, social reality) is generally considered to be “institutionalised” – what this means is that it does not directly depend on collective recognition or action, but can instead depend on something that depends on something that depends on something… and so on.

There are two views about the operation of legal rules in this connection: either they apply ‘automatically’ and legal reasoning reconstructs something that is already the case, or they do not apply automatically and legal reasoning constructs something that wasn’t already the case.

Either way: the operation of legal rules creates new states of affairs, that is, new facts. Applying a legal rules brings about new facts. Let’s say I buy a house, thereby gaining the status “house owner”. There is a rule that holds that house owners have to shovel snow in front of their house. I now have an obligation to shovel snow (when it snows). The fact that I have this obligation is a new fact that did not exist in the world before this rule became applicable and applied to my case. Law has created something new and thereby changed reality.

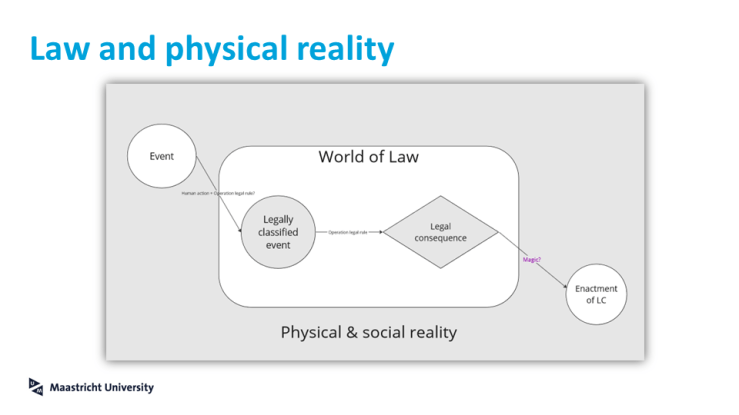

I’ve tried to create a visual on how law interacts with physical reality in our world (on a particular understanding of law – if you’re interested, have a look at e.g. JC Hage, The (onto)logical structure of law: a conceptual toolkit for legislators, in Michal Araszkiewicz and Krzysztof Pleszka, Logic in the theory and practice of lawmaking, Cham: Springer 2015, p. 3-48). If something happens in physical reality (e.g. me buying a house, or hitting someone with a car), this may be translated (by operation of a legal rule) into the world of law, which is a(n institutionalised) part of social reality. There, a legal consequence may be attached to it – e.g. the obligation to shovel snow, or to pay for damages). But we’ve just seen that law doesn’t outright affect reality – so how does the translation from legal consequence to enactment of the legal consequence occur?

On the slide, it says “magic?”. The precise (cognitive) mechanisms by which law impacts human behaviour and thereby “visible” physical reality (interpreted socially) are not yet known. But if it is indeed a case of cognitive mechanisms, of neurons firing, which seems a pretty solid conclusion to me, then it isn’t magic so much as just law impacting physical reality in a way that we cannot immediately perceive with our senses.

And if that’s the case, law in our world directly affects physical reality as well.